Atomic Layer Deposition ALD

This content was adapted from Atomic Layer Deposition by Barron, A., Connexions Web site. [1] Jul 13, 2009. This module was developed as part of the Rice University course CHEM-496: Chemistry of Electronic Materials. This module was prepared with the assistance of Julie A. Francis. It is reused under a creative commmons license.

Introduction

The growth of thin films has had dramatic impact on technological progress. Because of the various properties and functions of these films, their applications are limitless especially in microelectronics. These layers can act as superconductors, semiconductors, conductors, insulators, dielectric, or ferroelectrics. In semiconductor devices, these layers can act as active layers and dielectric, conducting, or ion barrier layers. Depending on the type of film material and its applications, various deposition techniques may be employed. For gas-phase deposition, these include vacuum evaporation, reactive sputtering, chemical vapor deposition (CVD), especially metal organic CVD (MOCVD), and molecular beam epitaxy (MBE). Atomic layer deposition (ALD), originally called atomic layer epitaxy (ALE), was first reported by Suntola et al. in 1980 for the growth of zinc sulfide thin films to fabricate electroluminescent flat panel displays.

ALD refers to the method whereby film growth occurs by exposing the substrate to its starting materials alternately. It should be noted that ALE is actually a sub-set of ALD, in which the grown film is epitaxial to the substrate; however, the terms are often used interchangeably. Although both ALD and CVD use chemical (molecular) precursors, the difference between the techniques is that the former uses self limiting chemical reactions to control in a very accurate way the thickness and composition of the film deposited. In this regard ALD can be considered as taking the best of CVD (the use of molecular precursors and atmospheric or low pressure) and MBE (atom-by-atom growth and a high control over film thickness) and combining them in single method. A selection of materials deposited by ALD is given in Table 1. Table 1: Examples of thin film materials deposited by ALD including films deposited in epitaxial, polycrystalline or amorphous form. Adapted from M. Ritala and M. Leskel, Nanotechnology, 1999, 10, 19.

| compound class | Examples |

|---|---|

| II–VI compounds | ZnS, ZnSe, ZnTe, ZnS1−xSex, CaS, SrS, BaS, SrS1−xSex, CdS, CdTe, MnTe, HgTe, Hg1−xCdxTe, Cd1−xMnxTe

|

| II–VI based thin-film electroluminescent (TFEL) phosphors | ZnS:M (M = Mn, Tb, Tm), CaS:M (M = Eu, Ce, Tb, Pb), SrS:M (M = Ce, Tb, Pb, Mn, Cu) |

| III–V compounds | GaAs, AlAs, AlP, InP, GaP, InAs, AlxGa1−xAs, GaxIn1−xAs, GaxIn1−xP |

| Semiconductors/dielectric nitrides | AlN, GaN, InN, SiNx |

| Metallic nitrides | TiN, TaN, Ta3N5, NbN, MoN |

| Dielectric oxides | Al2O3, TiO2, ZrO2, HfO2, Ta2O5, Nb2O5, Y2O3, MgO, CeO2, SiO2, La2O3, SrTiO3, BaTiO3 |

| Transparent conductor oxides | In2O3, In2O3:Sn, In2O3:F, In2O3:Zr, SnO2, SnO2:Sb, ZnO, |

| Semiconductor oxides | ZnO:Al, Ga2O3, NiO, CoOx |

| Superconductor oxides | YBa2Cu3O7-x |

| Fluorides | CaF2, SrF2, ZnF2 |

How ALD works

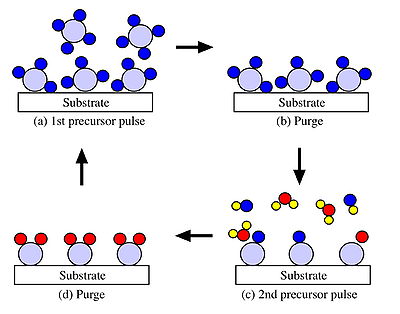

The premise behind the ALD process is a simple one. The substrate (amorphous or crystalline) is exposed to the first gaseous precursor molecule (elemental vapor or volatile compound of the element) in excess and the temperature and gas flow is adjusted so that only one monolayer of the reactant is chemisorbed onto the surface (Figure 1a). The excess of the reactant, which is in the gas phase or physisorbed on the surface, is then purged out of the chamber with an inert gas pulse before exposing the substrate to the other reactant (Figure 1b). The second reactant then chemisorbs and undergoes an exchange reaction with the first reactant on the substrate surface (Figure 1c). This results in the formation of a solid molecular film and a gaseous side product that may then be removed with an inert gas pulse (Figure 1d).

The deposition may be defined as self-limiting since one, and only one, monolayer of the reactant species remains on the surface after each exposure. In this case, one complete cycle results in the deposition of one monolayer of the compound on the substrate. Repeating this cycle leads to a controlled layer-by-layer growth. Thus the film thickness is controlled by the number of precursor cycles rather than the deposition time, as is the case for a CVD processes. This self-limiting behavior is the fundamental aspect of ALD and understanding the underlying mechanism is necessary for the future exploitation of ALD.

One basic condition for a successful ALD process is that the binding energy of a monolayer chemisorbed on a surface is higher than the binding energy of subsequent layers on top of the formed layer; the temperature of the reaction controls this. The temperature must be kept low enough to keep the monolayer on the surface until the reaction with the second reactant occurs, but high enough to re-evaporate or break the chemisorption bond. The control of a monolayer can further be influenced with the input of extra energy such as UV irradiation or laser beams. The greater the difference between the bond energy of a monolayer and the bond energies of the subsequent layers, the better the self-controlling characteristics of the process.

Basically, the ALD technique depends on the difference between chemisorption and physisorption. Physisorption involves the weak van der Waal's forces, whereas chemisorption involves the formation of relatively strong chemical bonds and requires some activation energy, therefore it may be slow and not always reversible. Above certain temperatures chemisorption dominates and it is at this temperature ALD operates best. Also, chemisorption is the reason that the process is self-controlling and insensitive to pressure and substrate changes because only one atomic or molecular layer can adsorb at the same time.

Equipment for the ALD process

Equipment used in the ALD process may be classified in terms of their working pressure (vacuum, low pressure, atmospheric pressure), method of pulsing the precursors (moving substrate or valve sources) or according to the types of sources. Several system types are discussed.

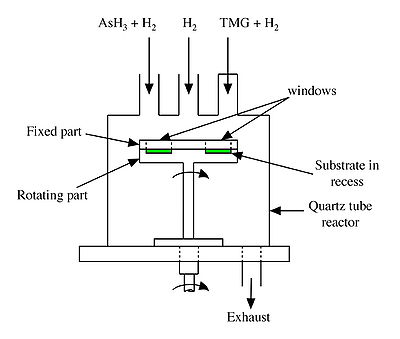

In a typical moving substrate ALD growth system (Figure 2) the substrate, located in the recess part of the susceptor, is continuously rotated and cuts through streams of the gaseous precursors, in this case, trimethylgallium [TMG, Ga(CH3)3] and arsine (AsH3). These gaseous precursors are introduced through separate lines and the gases come in contact with the substrate only when it revolves under the inlet tube. This cycle is repeated until the required thickness of GaAs is achieved. The exposure time to each of the gas streams is about 0.3 s.

ALD may be carried out in a vacuum system using an ultra-high vacuum with a movable substrate holder and gaseous valving. In this manner it may be also equipped with an in-situ LEED system for the direct observation of surface atom configurations and other systems such as XPS, UPS, and AES for surface analysis.

A lateral flow system may also be employed for successful ALE deposition. This uses an inert gas flow for several functions; it transports the reactants, it prevents pump oil from entering the reaction zone, it valves the sources and it purges the deposition site between pulses. Inert gas valving has many advantages as it can be used at ultra high temperatures where mechanical valves may fail and it does not corrode as mechanical valves would in the presence of halides. This method is based on the fact that as the inert gas is flowing through the feeding tube from the source to the reaction chamber, it blocks the flow of the sources. Although in this system the front end of the substrate receives a higher flux density than the down-stream end, a uniform growth rate occurs as long as the saturation layer of the monoformation predominates. This lateral flow system effectively utilizes the saturation mechanism of a monolayer formation obtained in ALE. Depending on the properties of the precursors used, and on the growth temperature, various growth systems may be used for ALE.

Requirements for ALD growth

Several parameters must be taken into account in order to assure successful ALD growth. These include the physical and chemical properties of the source materials, their pulsing into the reactor, their interaction with the substrate and each other, and the thermodynamics and volatility of the film itself.

Source molecules used in ALD can be either elemental or an inorganic, organic, or organometallic compound. The chemical nature of the precursor is insignificant as long as it possesses the following properties. It must be a gas or must volatilize at a reasonable temperature producing sufficient vapor pressure. The vapor pressure must be high enough to fill the substrate area so that the monolayer chemisorption can occur in a reasonable length of time. Note that prolonged exposure to the substrate can cause the precursor to condense on the surface hindering the growth. Chemical interaction between the two precursors prior to chemisorption on the surface is also undesired. This may be overcome by purging the surface with an inert gas or hydrogen between the pulses. The inert gas not only separates the reactant pulses but also cleans out the reaction area by removing excess molecules. Also, the source molecules should not decompose on the substrate instead of chemisorbing. The decomposition of the precursor leads to uncontrolled growth of the film and this defeats the purpose of ALD as it no longer is self-controlled, layer-by-layer growth and the quality of the film plummets.

In general, temperature remains the most important parameter in the ALD process. There exists a processing window for ideal growth of monolayers. The temperature behavior of the rate of growth in monolayer units per cycle gives a first indication of the limiting mechanisms of an ALD process. If the temperature falls too low, the reactant may condense or the energy of activation required for the surface reaction may not be attained. If the temperature is too high, then the precursor may decompose or the monolayer may evaporate resulting in poor ALD growth. In the appropriate temperature window, full monolayer saturation occurs meaning that all bonding sites are occupied and a growth rate of one lattice unit per cycle is observed. If the saturation density is below one, several factors may contribute to this. These include an oversized reactant molecule, surface reconstruction, or the bond strength of an adsorbed surface atom is higher when the neighboring sites are unoccupied. Then the lower saturation density may be thermodynamically favored. If the saturation density is above one, then the undecomposed precursor molecules form the monolayer. Generally, ideal growth occurs when the temperature is set where the saturation density is one.

Advantages of ALD

Atomic layer deposition provides an easy way to produce uniform, crystalline, high quality thin films. It has primarily been directed towards epitaxial growth of III-V (13-15) and II-V (12-16) compounds, especially to layered structures such as superlattices and superalloys. This application is due to the greatest advantage of this method, it is controllable to an accuracy of a single atomic layer because of saturated surface reactions. Not only that, but it produces epitaxial layers that are uniform over large areas, even on non-planar surfaces, at temperatures lower than those used in conventional epitaxial growth.

Another advantage to this method that may be most important for future applications, is the versatility associated with the process. It is possible to grow different thin films by choosing suitable starting materials among the thousands of available chemical compounds. Provided that the thermodynamics are favorable, the adjustment of the reaction conditions is a relatively easy task because the process is insensitive to small changes in temperature and pressure due to its relatively large processing window. There are also no limits in principle to the size and shape of the substrates.

One advantage that is resultant from the self-limiting growth mechanism is that the final thickness of the film is dependent only upon the number of deposition cycles and the lattice constant of the material, and can be reproduced and controlled. The thickness is independent of the partial pressures of the precursors and growth temperature. Under ideal conditions, the uniformity and the reproducibility of the films are excellent. ALE also has the potential to grow very abrupt heterostructures and very thin layers and these properties are in demand for some applications such as superlattices and quantum wells.

Bibliography

- D. C. Bradley, Chem. Rev., 1989, 89, 1317.

- M. Ritala and M. Leskel, Nanotechnology, 1999, 10, 19.

- M. Pessa, P. Huttunen, and M. A. Herman, J. Appl. Phys., 1983, 54, 6047.

- T. Suntola and J. Antson, Method for producing compound thin films, U.S. Patent 4,058,430 (1977).

- M. A. Tischler and S. M. Bedair, Appl. Phys. Lett., 1986, 48, 1681.